Burnt Lake is a six acre lake in the Mt. Hood Wilderness west of Mt. Hood. It is a very popular destination for both day hikers and backpackers since the hike in is only 3.5 miles one way. The fact that Mt. Hood serves as a beautiful backdrop to the lake certainly doesn’t hurt.

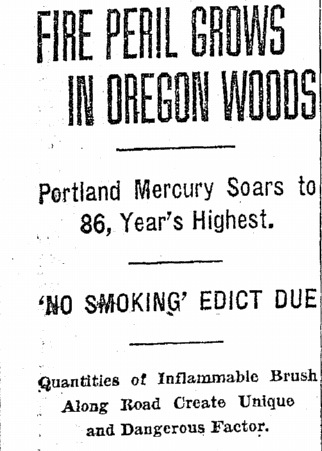

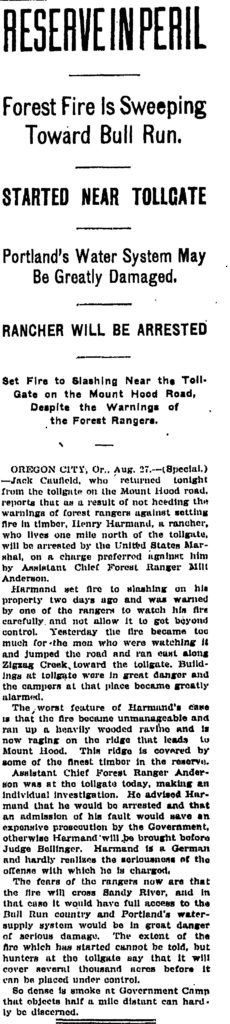

Looks pretty green, so how did it get its name? Turns out it wasn’t always green, and the name comes from when this area burned in an early 20th Century wildfire. An article in the August 28, 1904 edition of the Oregonian discusses a wildfire started by rancher Henry Harmand who lived “one mile north of the tollgate”. “Harmand set fire to slashing on his property two days ago and was warned by one of the rangers to watch his fire carefully and not allow it to get beyond control. Yesterday the fire became too much for the men who were watching it and jumped the road and ran east along Zigzag Creek, toward the tollgate.”

The article goes on to say “the extent of the fire which has started cannot be told, but hunters at the tollgate say that it will cover several thousand acres before it can be placed under control”. The smoke in Government Camp was so dense “that objects half a mile distant can hardly be discerned.”

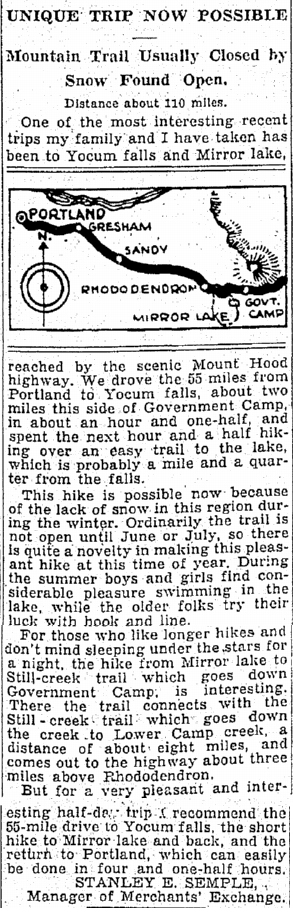

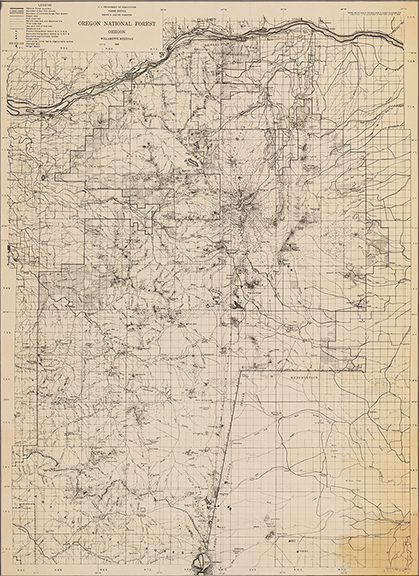

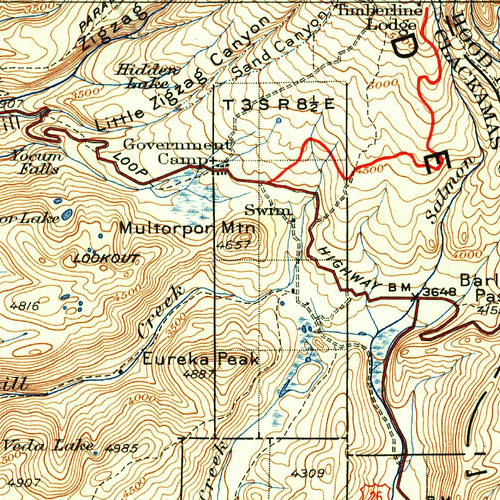

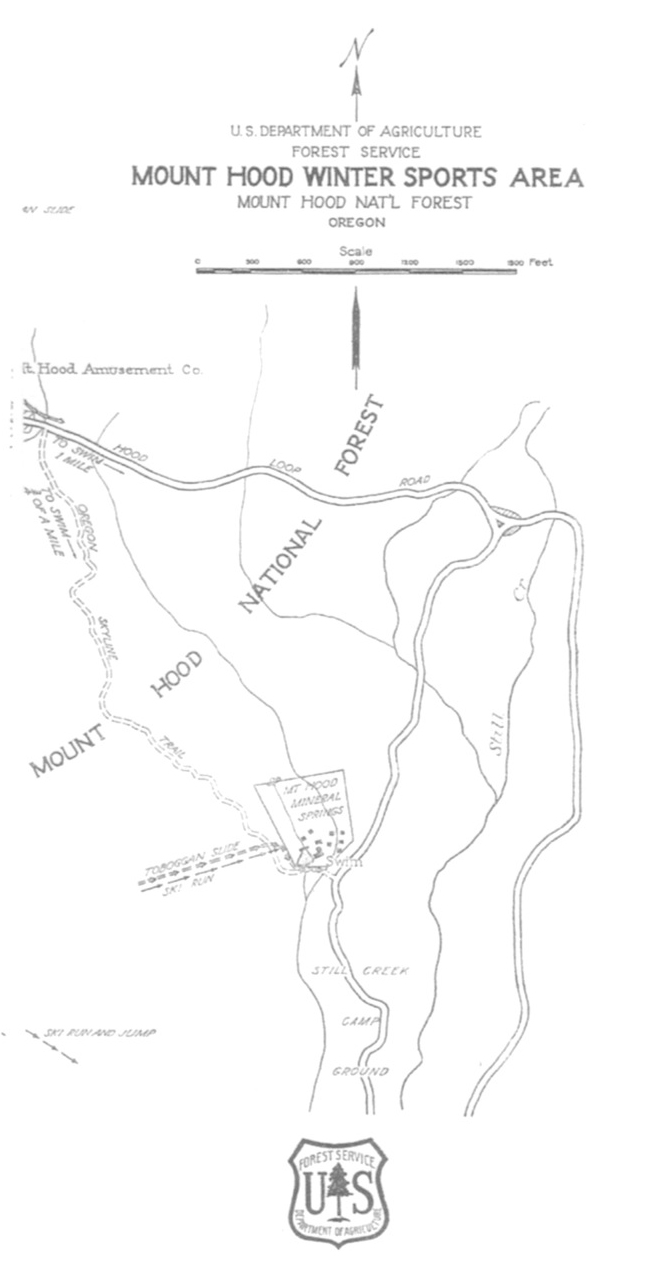

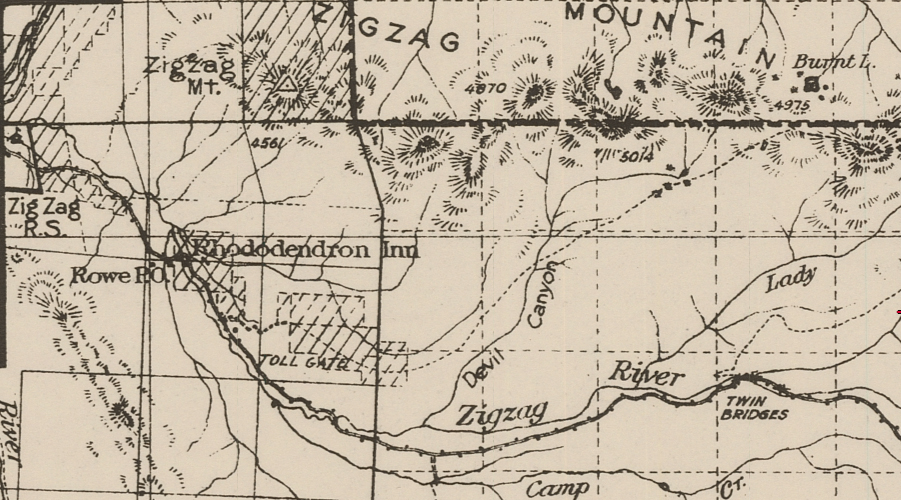

Here is a map of the area from the 1911 Mt. Hood National Forest map, showing Burnt Lake at upper right, Tollgate at lower left, and Zigzag Ranger Station at far left:

Unfortunately that is the last article about it. No more mention of Harmand or the fire. But additional information can be found in Hiking Mount Hood National Forest (2002), by Marcia Sinclair:

Ralph Lewis and John Cooper worked for the Forest Service in 1905. Twenty-three years old, they had grown up as children of the first homestreaders living around the mountain. Cooper Spur was named for John Cooper’s father who helped build the road up the mountain. Ralph and John named many landmarks in the country between Bull Run Lake and Zigzag Mountain. They knew every stream and rock outcrop. Their colorful story of the Clear Creek Fire was recorded when both men were elderly and is on file at Zigzag Ranger Station.

According to Ralph and John, in late August of 1906 a homesteader near Clear Creek was burning logs. He went out for a Sunday and left the fire burning. A west wind came up and “throwed it” across his fire lines into brush and dead timber. The fire became explosive. The ranger at Clear Fork “lost his head and put all his supplies in the creek and went for help.”

Gathering firefighters in 1906 was no small task. There were no roads through this country, only a few trails. There were no phones and people were spread out across miles of forest. As was the custom then, “winos” were rounded up on Burnside Street in Portland and brought by wagon to the mountain to fight fire.

While rangers tried to round up firefighters, the Clear Creek Fire spread from what is now McNeil Campground east across Old Maid Flat, up Zigzag Mountain and toward Lost Lake. Then the wind shifted. Blowing from the east, it took the fire back across its own path. According to Ralph and John it stopped at “green timber.”

This wasn’t the first fire through here. A series of fires had swept across the south and west flanks of Mt. hood starting in 1902. It was in a 1904 blaze that Burnt Lake got its name. Even before these fires came through, the country was open enough that people traveled on foot or horseback through an open understory. The trail from Lost Lake to the Sandy River wasn’t built until 1903.

Indians used fire to maintain the plants they used most for food and medicine and sacred ceremonies. They regularly burned the forest late in the season, timing it so that the first fall rains would extinguish the blaze. This cleared shrubs and seedlings, but didn’t burn hot enough to kill the larger trees. According to Ralph, “It was said the Indians liked to see things burned off on account of hunting, and people to this day think that if the Indians was running things, instead of the Forest Service, we’d have less of these big fires.”

By the turn of the century, more people were using the forest for homesteading and recreation. As a result, fires became common during the hot summer months. A 1903 government report on forest conditions in the Cascade Range state, “These burns have taken place in all parts of the reserve, and so cannot be attributed to any particular cause, but rather demonstrate that wherever men go fires follow.”

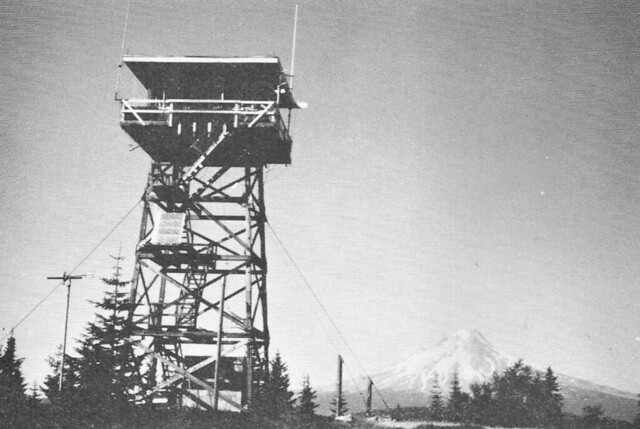

By 1906, firefighting had become a Service. That year the rangers at Mt. Hood started posting lookouts. Ralph was one of the first. Thus began a hundred-year history of preventing and controlling forest fires.

I wonder if these two stories aren’t one in the same. Since Ralph and John were recounting their story many years later it’s possible that they got the year wrong and were referring to the fire mentioned in the 1904 article. I don’t see any mention of a “Clear Creek Fire” (or indeed any August wildfire near Mt. Hood) in the newspaper in 1906. In any case, a wildfire that swept through this area gave Burnt Lake its name.

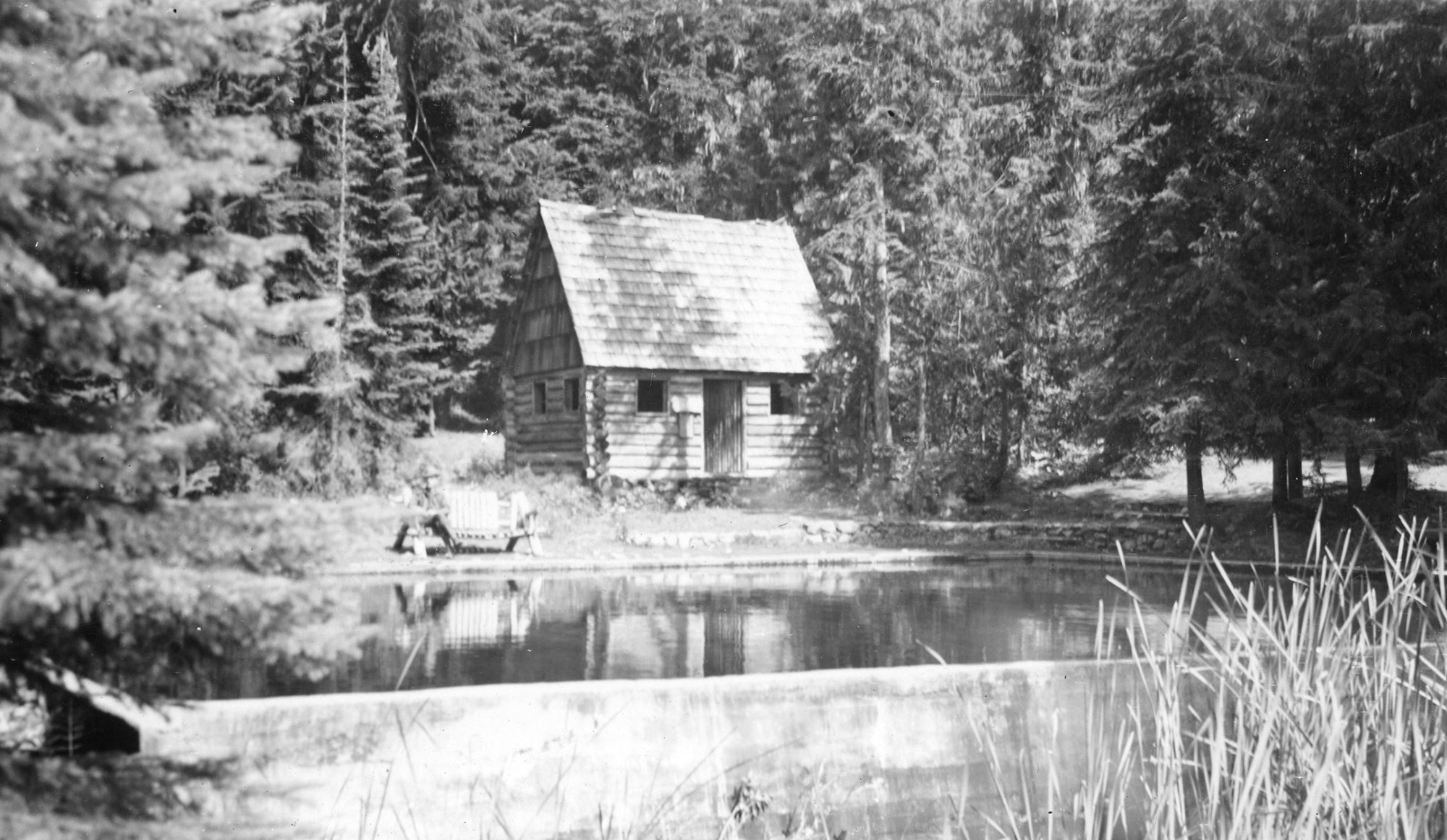

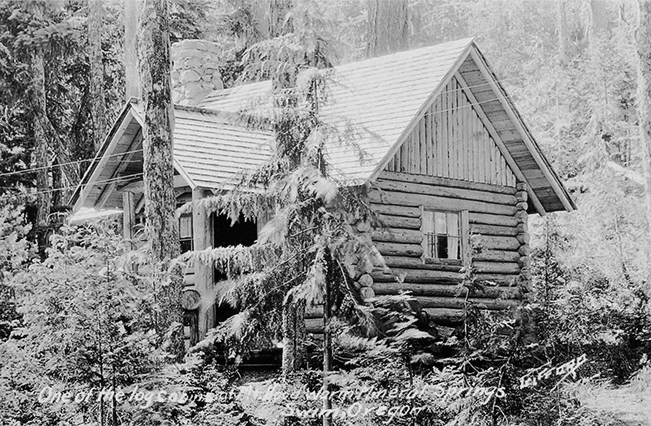

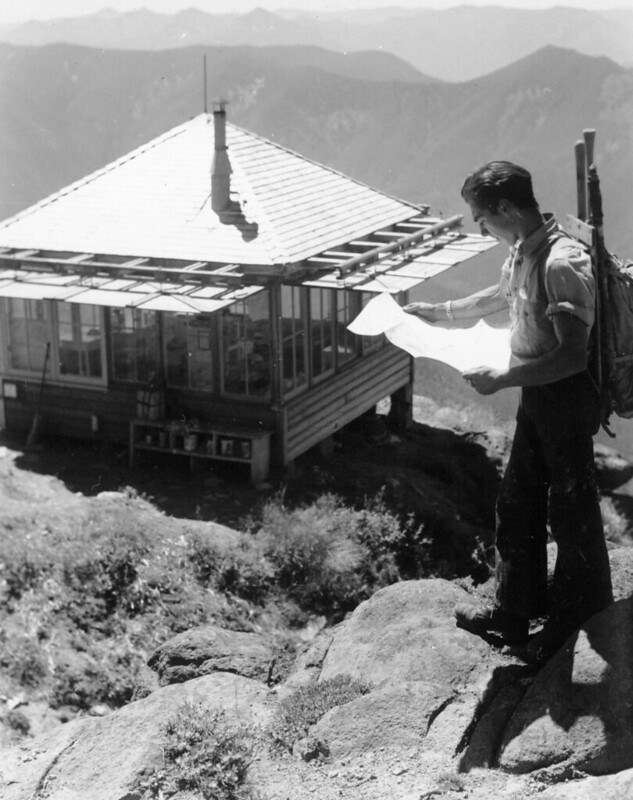

By the time the 1931 Mt. Hood National Forest map was printed a trail to Burnt Lake had been constructed. That map also shows the two lookouts on nearby Zigzag Mountain that were built sometime in the 1930s. The two spots became known as West Zigzag and East Zigzag. The L-4 ground cabin at West Zigzag was one of those unusual lookouts that was not on a peak with 360-degree views. It sat on a ridge with a view to the south. It is pictured here in this undated photo:

Photo credit: George Henderson

The lookout was removed in the 1960s, but you can still hike there. Here is roughly the same shot as the one above, in 2014:

The footings are still there:

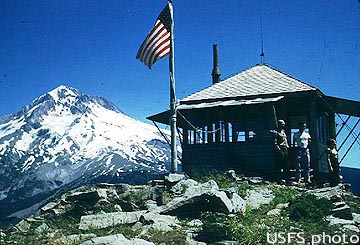

East Zigzag is right above Burnt Lake, and it also had an L-4 ground cabin, pictured here in 1953:

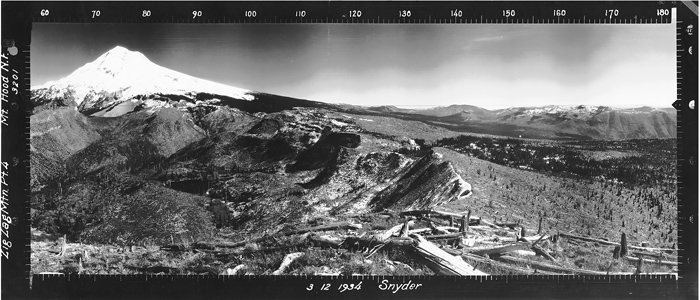

Panorama photos were taken in 1934 and you can see the effects of logging and fires on the surrounding forest:

The photo below is hanging in the Zigzag Ranger Station and didn’t have a date, but it looks to be from the 1960s based on that helicopter. This is a view looking west over Burnt Lake to East Zigzag, where the lookout still stands:

That lookout was removed by burning in the 1960s:

Hikers can still visit the spot by continuing past Burnt Lake or by hiking up from Devil’s Canyon, from a trailhead at the end of very rough Road 207. Here is what the site looked like in 2018:

You can see some burnt-out cedar trees on the hike to Burnt Lake, presumably leftover from that long ago fire.

As of 1964 this entire area – including Burnt Lake and Zigzag Mountain – is part of the Mt. Hood Wilderness.